| Radiology Room |

| Ultrasound Room |

| Surgery Room |

| Laboratory Room |

| Comprehensive Room |

| Pediatrics Room |

| Dental Room |

| Medical operation instruments |

| Hospital Furniture |

| Medical supplies |

News Center

Farm workforce withers as young people leave

Lure of city lights draws youth away as parents remain to work the land, He Na and Han Junhong report from Gongzhuling in Jilin province.

He may not need it any more, but retired farmer Li Shiwu still refuses to be parted from his farm tool.

|

|

|

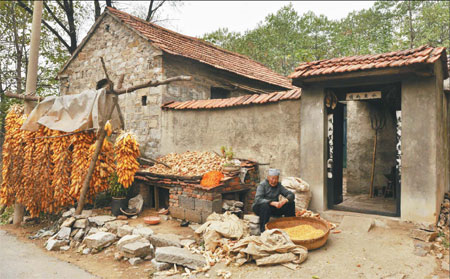

When the plowing season starts across China in spring, most farmers who take to the fields will be in their 50s or older. For people in towns and villages that rely on the strength of their agricultural industry, such as this elderly corn farmer in Xixiang village, Shandong province, the lack of interest among younger people in farming is a worrying trend. Land transfers are one solution, while experts also want to see more training offered to farmers. [Photo/China Daily] |

"My wife threw it away once," the 70-year-old said as he carefully polished the tool. "It was just after we'd agreed to rent out our land. I was very angry and made her get it back."

Li has spent his entire working life toiling in the fields of Nanxing village in Northeast China and had hoped one of his daughters would take over the family farm when he retired. However, all six refused to return from the nearby city where they live.

|

|

|

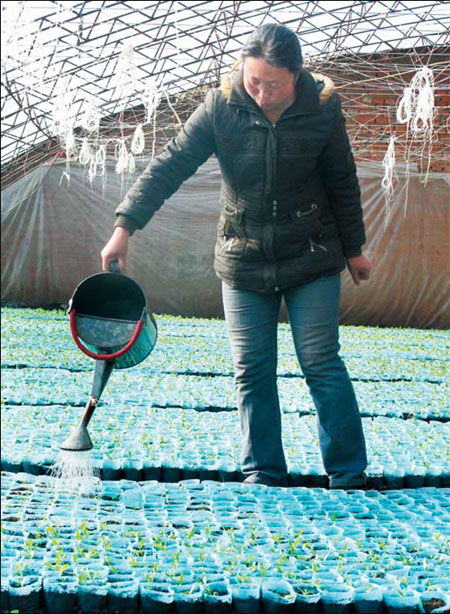

Ji Chunyan in one of the five greenhouses built on land she rented from her brother and sister in Daling, Jilin province. Her family can now earn 200,000 yuan in a year. [Photo/China Daily] |

"Most youngsters today hate farm work; they complain that it's too hard, dirty and pays too little," the pensioner said. "My daughters and sons-in-law think so, not to mention my grandchildren. They don't even want to visit during holidays because they say it's boring."

As the average age for a farmer increases, finding young people who are willing to pick up the baton has become a pressing problem in rural areas, which cannot compete with wages and lifestyles offered in cities.

Yet, community leaders say there is a solution: liberating farmers from the land.

Since the 1980s, young people - mostly men - have been flocking to cities for better opportunities, leaving the elderly and infirm behind to take care of the crops. Even government incentives for farmers such as subsidies, seeds and machinery have been unable to stem the flow.

Data from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security show the migrant workforce reached 242 million in 2010, more than double the 98 million recorded five years earlier.

Li, the retired farmer in Jilin province, said his daughters all moved to cities soon after they were married. "My youngest works at an automobile factory in Changchun," he said. "She told me that the money she earns in three months would take me an entire year sweating in the fields."

Those born in the countryside after the 1980s are often referred to as second-generation farmers, but in reality the majority either do not like working in the fields or have no knowledge about how to run a farm.

"I like life in the city," said Sun Wei, 29, who was born and raised in a Jilin village but now works as a car salesman in Beijing. "I know nothing about crops, so why would I go back? I'd sooner die than be told I had to go to bed before 9 o'clock every night."

Aging industry

Like many aging laborers, Li was reluctantly forced into retirement by ill health. He produced a box containing various medicines for arthritis, high blood pressure and diabetes.

When his daughters refused to return home, he began to fear that his land may go unused this spring and contacted Nanxing's village committee for help. That was when he got the idea to rent out the space.

"It's how the government in (nearby Daling) town tackled the problem of empty villages," explained village head Ma Xiaobo, who had just returned from a meeting in Daling about land transfers, which he described as a way to liberate laborers and consolidate land in the hands of experienced farmers.

He suggested Li hand over his land to a younger farmer with better technology who could increase the yield. That way, Li and his wife would receive an income of 3,000 yuan a year and the land would not go to waste.

"I saw lots of barren land on the roadside last year," said Ma, who added that out of a population of 2,200, at least 800 people had left for cities. "The amount of (arable) land is decreasing year by year in China, so to see good land abandoned is a real pity."

Yao Weibo, leader of the government in Daling, said the 15 villages under his jurisdiction have all experienced the same problem as Nanxing.

When the plowing season starts in spring, most farmers who take to the fields will be in their 50s or older. For an area that relies on the strength of its agricultural industry, the lack of interest among younger people is worrying.

"This is a nationwide issue, one that can't be solved by a low-level official like me," Yao said. However, he agreed land transfers are a good short-term solution.

"To increase farmers' incomes, we must liberate them from the land," he said. "At the moment, a young man can either earn 50 yuan ($8) a day on a construction site or 10,000 yuan a year at most by farming 1 hectare.

"People should be encouraged to go out and improve their lives," he added, "but that doesn't mean their farmland must be abandoned."

Technology has helped ease the burden; a job that once took three people to do can now be done by one. However, experts say the use of advanced machinery can be difficult on small, scattered patches of land, affecting efforts to popularize it.

"Realizing large-scale land management is a win-win deal," Yao added. "Landowners receive rent, sometimes double their previous income, and tenants can expand production and earn more."

Improving lives

Ji Chunyan's family is among those already benefiting from the land transfer system in Daling.

After renting adjoining pieces of land from her brother and sister, both migrant workers, she built five greenhouses to grow high-quality vegetables. She now supplies produce and seedlings to Wal-Mart supermarkets, among others, and can earn up to 200,000 yuan a year.

"If it wasn't for the land I rent (slightly more than 2 hectares), my family would still be struggling with debts," said Ji, 47. "Even though my husband and I worked day and night, our lives before were very hard, especially as we had two sons at college.

"Farmers can't get rich simply growing crops on the land given to them, especially as the government subsides are often swallowed up by sharp increases in the prices of seeds, fertilizer and agricultural tools."

Another beneficiary of the system is Yan Rong, who began renting abandoned land in Linxi village when people left for jobs in coastal cities or in South Korea.

By carefully choosing the right locations for different crops corn in higher spots and rice in waterlogged fields his total output rose to 100,000 kilograms. He said that with cash in his pocket, he was able to invest in machinery to increase productivity, as well as add a fishpond and a sty for more than 200 pigs.

Although younger people are keen on the idea of renting land, convincing elderly farmers to play silent landlords can be more difficult.

Li Shixun is 65 years old, yet he said he has no intention of letting anyone else use his 0.7 hectares. "I've been living in the countryside all my life," said the farmer, whose four daughters all have stable jobs in the city. "I'd feel uncomfortable in the city, so as long as I can walk I'll take care of the land myself."

Learning lessons

Rong Tingzhao at the Chinese Academy of Engineering is an advocate of the ranch model transferring land on a voluntary and compensatory basis to develop scale operations and said he believes it is an "inevitable demand of modern agricultural development".

In a recent essay, Zhang Zhizhong, an agricultural expert at the State Council's Development Research Center, also suggested authorities revise the rules on rural-land contract management to ease labor shortages.

Meanwhile, officials in Huoqiu, a county in East China's Anhui province, have set up 32 crop-protection teams professionals with training in agriculture to help farmers in their fields and offer advice. Many provinces are now attempting to learn from the experience.

"The future of farming is well-educated professionals who have a good grasp of agriculture and marketing techniques," said Yao, head of Daling town. "They are vital to securing China's crop supplies."